Greece Remains on Track

September 22, 2015 9:28 am (EST)

- Post

- Blog posts represent the views of CFR fellows and staff and not those of CFR, which takes no institutional positions.

More on:

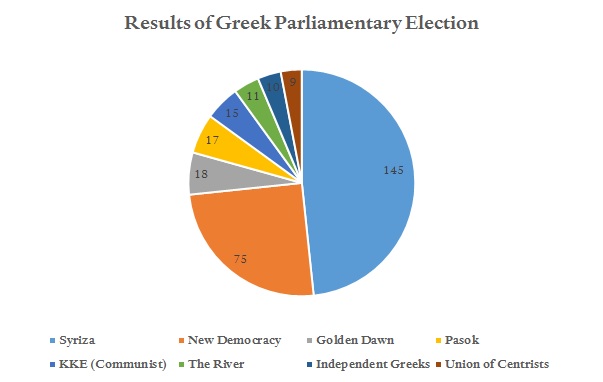

The Greek elections on Sunday returned the Syriza-led coalition government, a modest surprise following polls showing a close race that might have left a deadlocked parliament. Most commenters took the result as positive for Greece’s reform effort. Certainly, the government now has a strengthened mandate to implement the program that it agreed to in August. The program’s first review, now likely in November has some tough issues (e.g., pensions, banking recapitalization) but disagreements are likely to be navigated, setting the basis for a negotiation on debt relief and the terms of an International Monetary Fund (IMF) program. Most importantly, the ongoing European immigration crisis and other pressures on European decision making (e.g., “Brexit”) likely have reduced the appetite of even Greece’s toughest critics for a confrontation with the government. All this points to the needed forbearance to keep the program on track.

There are a few reasons for caution, which provide perspective on why I still believe that ultimately “Grexit” remains the most likely outcome and the best chance for Greece to restore growth over the longer term.

Pensions and banking. First review of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) program will see the government pushed to take further steps on pension reform, one of the toughest areas politically for the Tsipras government. On the banking side, there are significant differences over the size of the bank recapitalization (the IMF reportedly would like to see a larger recapitalization than what the Greek government has called for, hoping to provide a buffer against future downside risks).

Fiscal slippages and financing. While anecdotally, there has been a pickup in tax collection, the August data shows that revenue remains 11.9 percent below target. Fiscal targets are being met overall, through a massive reduction in spending that is unlikely to be sustainable. Part of this improvement, further, relies on cash-basis accounting, and the likely continued accumulation of arrears flatters the books. Given the economic carnage associated with the showdown with creditors this summer, there likely will be slippages from what was assumed and there will be a difficult debate over whether Greece should be required to take additional austerity measures.

Official creditor disputes. If Greece is not required to take additional fiscal measures, and as a result the financing required for the program exceeds the predicted €86 billion, then who will pay? The IMF has already signaled their willingness to lend depends on “explicit and concrete” debt relief from other official creditors, an argument that I have linked to a desire to limit their own financing. Without a long moratorium on repayments, perhaps of 30 years, or a reduction in the value of the debt, the burden will become unmanageable, the IMF has argued. But even if European creditors meet the IMF demand, there could be a residual financing need in excess of what the IMF is comfortable providing. While the agreement in principle calls on the Europeans to meet any financing shortage, the risk in having the IMF go after the debt relief deal is that it becomes the de facto lender of last resort.

In sum, Sunday’s election eliminates one set of risks facing the Greek effort to return to growth in the eurozone. Harder tests remain.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store